The stark difference between Russell’s and Whitehead’s Principia Mathematica and Whitehead’s Later Thought in “Process and Reality.”

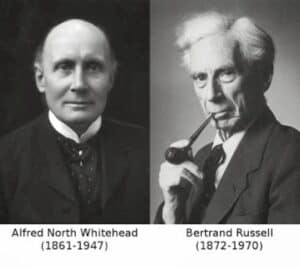

It has always been a puzzle to me how Whitehead could have written, with Bertrand Russell, the two-volume Principia Mathematica in 1911, in which they sought to base the principles of mathematics on those of logic, and then, years later, write his own highly speculative Process and Reality in 1929 (revised version 1979). The two works seem diametrically different in both subject matter and style, with the former narrowly defining the abstract principles of logic and mathematics and the latter a very creative venture into speculative metaphysics.

I have read several authors who offer what I take to be either offhand or weak explanations for why Whitehead would seemingly launch into a highly speculative effort to describe the dynamic forces and principles that govern the shape and dynamics of all reality. No one seems willing to address the obvious contrast in style and content between these two highly significant works. Granted, the 1979 version (the “corrected edition,” edited by David Ray Griffin and Donald Sherburne) has been carefully corrected and addresses many of the difficulties in the original. Yet none of this explains the diametric difference between the two original works, both in style and content.

My point is that there is a clear and strong contrast between Whitehead’s earlier and later work. The only thing that springs to mind to explain this stark difference is that some sort of dramatic change took place in the way Whitehead came to think about the nature of reality. Why this change came about remains unclear. One might perhaps suggest that Whitehead’s move to America and to Harvard altered his imagination and his speculative grasp of the nature of reality. Process, rather than the static symbolism of logic, physics, and mathematics, clearly took center stage in his thought.

In his Preface to Process and Reality, Whitehead “repudiated” what he called the “negative doctrine,” embodied in distrust of speculative philosophy, the assumption that language is an adequate expression of thought, and the “Kantian doctrine” of the objective world as a purely theoretical construct of subjective experience, without a clue as to how and/or why he came to think so. He claims, on the contrary, that his “positive doctrine” of “relatedness” and “becoming,” as the forces that drive the advance of the world (Pages xi and xii), should be considered more fundamental.

Right off the bat, the only guess I can make as to the genesis of this turnaround in Whitehead’s thought is the developments in atomic theory that took place during and near the end of World War Two. As we all recall from our high school science classes, the pivotal formula that brought the war to an end is E = mc^2, where E is energy, m is mass, and c is the speed of light. Simplistically, this might be the principle Whitehead had in mind: that energy, not matter, constitutes the most real aspect of reality. This might have been the clue that set Whitehead’s creative mind in motion toward what we call “process philosophy”. Then he set about to track and describe what he thought the dynamics of cosmic energy might be in Process and Reality.

After some introductory remarks, Whitehead presented a chart of what he took to be the patterns governing the dynamics of energy in his Table of Contents, Chapter Two, “The Categorical Scheme” (p. 18). On page 18, Whitehead introduced the four main features of his new approach to understanding the nature of reality: “actual occasions,” sometimes called “actual entities,” “prehensions” of them, and “nexi,” which govern the interrelations among these key aspects of reality.

Whitehead then briefly explains the relationships among these key aspects of reality: “Actual entities involve each other by reason of their prehensions of each other. These are thus individual facts of the togetherness of the actual entities, which are real, individual, and particular in the same sense in which actual entities and the prehensions are real, individual, and particular. Any such particular fact of togetherness among actual entities is called a nexus…The ultimate facts of immediate actual experience are actual entities, prehensions, and nexus. All else is, for our experience, derivative abstraction.” (p. 20).

The core of Whitehead’s philosophy is energy rather than matter. He holds that the former generates the latter, not vice versa. This may be seen as a different interpretation of the E=mc² formula. For him, energy creates matter, not the other way around. Process is logically prior to matter and may also be experientially prior.

Whitehead’s unpacking of this paragraph constitutes the remainder of Process and Reality. I submit that careful attention to this paragraph replaces the physical understanding of reality with a fluid, dynamic “process” understanding, with energy in the cockpit rather than matter. Relational interaction among the foregoing aspects of reality animates and drives its dynamics, encompassing its human, natural, and spiritual dimensions. In Chapter Two of Part Five, Whitehead introduces the notion of God and explains divinity’s role in the development of world history with “creative and tender care,” as the “poet” of the world, even as that of our “fellow sufferer.”

This approach may provide insight into the radical turnabout in Whitehead’s later philosophy, as well as into his subsequent development of it in his classes and Gifford Lectures. It and he surely deserve the effort involved in such an undertaking, aimed at getting “behind” what Whitehead had in mind, thus shedding further light on John Cobb and David Griffin’s immensely valuable efforts to do so.