Jesus, His Brother James, and the Early Leadership of the Christian Church

In Chapter 15 of the Book of Acts in the New Testament, we find an account of how the early Christian believers organized themselves shortly after the resurrection of Jesus (around 49 AD). The main socio-politico-religious issue at that time during the birth of the Christian Church was the relationship between the new Christian believers and the traditional Jews. Peter was in charge, and he delivered a speech stating that Gentiles should be accepted into the New Community as equals with the already accepted Jewish believers (Acts 15:6-11).

His speech was followed by that of James, a brother of Jesus himself, who was already recognized as the leader of the new church community (Acts 12:17, 15:13). No specifics are provided about how James became the leader of the newly formed Christian Church. In his speech, James made an official declaration, quoting an Old Testament prophecy that God will accept believing Gentiles as his own children (Acts 15:16-18). The only requirement was that Gentile believers should avoid non-kosher foods and fornication (Lev. 17-18).

Nothing more is mentioned in the New Testament about James’s leadership of the early church, but tradition holds that he was martyred around 66 AD. In fact, it is unclear how many Jameses there were and who they were. It appears that Jesus had a brother named James, and that John, Jesus’ disciple and/or brother, also had a brother named John. In any case, it was John, the brother of Jesus, who became the accepted leader of the Jerusalem Church. There are numerous references to James in pseudepigraphal writings and other historical accounts from the period between the Testaments. It is often used as a substitute for the Hebrew name “Jacob.” Additionally, some writers mention a “James the Righteous One,” but it is unclear which biblical figure this refers to.

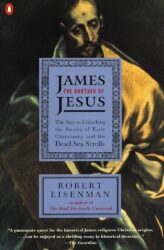

It is James, the brother of Jesus, that Robert Eisenman focuses on in his fascinating but confusingly written book, James: The Brother of Jesus and the Dead Sea Scrolls. In his efforts to depict Jesus as a deeply committed Jew—indeed, as an Essene—Eisenman seems to me to stretch his point too far. He tries to interpret Jesus as more of a Jewish Essene than a “Christian.” Moreover, it is almost impossible to follow his argument through the labyrinthine passages of his otherwise fascinating book. He is thoroughly committed to the idea that Jesus and others were loyal Jews, as opposed to Paul, whom he believes was a decidedly Roman Gentile hell-bent on separating the new Christian faith from that of the Jewish nation.

My graduate school friend James Charlesworth has made a strong case that Jesus was a “Very devout Jew who observed the Torah and whose life and thought must be understood within the context of Second Temple Judaism (The Historical Jesus, p.50). The truth of this claim does not, in any way, support the idea that Jesus, along with James and other disciples, opposed Paul and his view of who Jesus was, as Eisenman suggests. There were, of course, differences between Paul and the other Apostles, as shown in the Book of James and The Acts of the Apostles. However, this does not mean that Paul’s teachings were fundamentally opposed to those of James or any other Apostles. It is even possible, if not likely, that Jesus had strong Essene/Qumran connections. There were certainly significant differences between Paul and James, as clearly indicated in the Letter to the Galatians. But these differences don’t necessarily create a major rift between James and Paul.

It is clear from Paul’s letters and interactions with members of the early churches he established that they always included both Jewish and Gentile members. At times, Paul went out of his way to emphasize the unity between believers from both backgrounds, as his letters to the Romans and Galatians clearly show. Sometimes, Paul’s personality sometimes interfered with his strong commitment to keeping the new Christian churches united, and personality traits cannot be ignored. Nonetheless, his dedication to uniting Jewish and Gentile believers in the body of Christ remains evident.

The fact that the direction of the newly growing Church eventually diverged from this all-inclusive vision cannot be denied. Over time, the Christian religion became, under the Roman Emperors and Popes, essentially anti-Jewish, but the Jewish community also contributed to this split. Fortunately, the rift between the Roman Catholic Church and Judaism has been at least partially, if not significantly, addressed in the modern era. The Catholic Church has officially stated that Jews did not kill Jesus. While there is still a long way to go to heal the original divide between Judaism and Christianity, progress has been made—and continues to be made—toward overcoming this initial separation between these two Biblical faiths.